Mutual Recognition for New Americans Advances Democracy

Explore More

Sam Gill is Vice President for Communities and Impact at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. He gave the opening remarks on February 9, 2018 at the 6th Annual New Americans Campaign (NAC) Conference in Miami, FL.

I’m delighted and grateful for the opportunity to speak to you. I’m the Vice President for Communities and Impact at Knight Foundation, where I oversee our work in 26 cities around the country—many of them New Americans Campaign cities. More importantly, I’m the son of a naturalized citizen of the United States, my father—who is from India. I’m also the son of a naturalized citizen of Minnesota, my mother—who is from Wisconsin. Anyone from the Midwest knows the rivalry between Minnesota and Wisconsin is bitter, bitter ethnic strife.

My wife, who is a US citizen, is also a citizen of Brazil. Her parents, both doctors, delivered her in the US—in Memphis—when they were on research fellowships. I don’t think that’s what people typically mean when they say “chain migration.” My wife’s grandfather himself emigrated from Japan to Brazil in the 1930s. He’s 96 today and still doesn’t speak Portuguese. But he did ride the Sao Paulo subway into his 90s and has three daughters: a neonatologist (that’s my mother-in-law), an investment banker, and a college professor.

So, no, he’s not apologizing to anyone—in Japanese or Portuguese.

Knight Foundation was one of the founding funders of the New Americans Campaign, and it has been a source of tremendous pride at the foundation to see the campaign continue to grow and deliver for so many ‘new Americans,’ as it were. So, let me begin by congratulating all of you on the incredible work you’ve done and impact you’ve had.

Today, I want to talk about why Knight has invested in naturalization, and why now is a critical time to be doing the work you are doing. As I mentioned, Knight Foundation invests in 26 communities around the country. Our goal, based on the beliefs of our founders, is to support informed and engaged communities so that they can determine their futures. We see that as a key part of what makes our democracy work.

American communities, from their inception, have been defined not just by those who have been there for generations, but by newcomers as well—from around the country and around the globe. This is a commonplace but it’s worth repeating. Many of America’s greatest cities are iconic precisely because they are truly global beacons that bring people in from everywhere. And we know that, increasingly, towns and cities of all sizes are also becoming global beacons, to their benefit and to the benefit of the whole nation.

Knight’s role to play in this discussion has not been about what the right immigration policy or even ideology should be for this country. That discussion we leave to others. But we do know that residents who aren’t citizens can’t be fully engaged. Plain and simple, if you can’t vote and undertake the core duties of citizenship, you don’t have a full voice. And communities with voices that are silenced, by choice or by force, cannot be fully democratic communities. They cannot deliver democratic outcomes and, perhaps more importantly, they cannot rekindle continuously the embers of our democracy—the spirit and practice that makes our democracy vital. I’ll return to that idea in a moment.

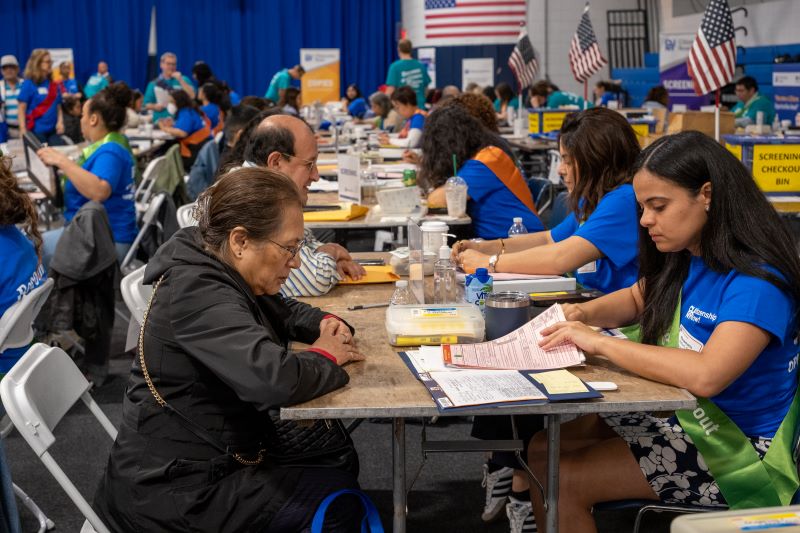

So Knight’s role has been to support your work. To work with the New Americans Campaign to enable you and others to help legal permanent residents take the final steps toward becoming citizens. The results have been exciting and promising. Since July 2011, you’ve helped people complete over 317,000 naturalization applications. If they all lived in one place, it would be just about tied with Lexington Kentucky as the 60th largest city in the US, and just ahead of St. Louis.

In the cities where Knight invests, you’ve helped complete 50,000 applications and saved communities an estimated fifty million dollars in application and legal fees. This is a tangible and direct impact on the places where Knight invests, where you work, and where we all live. These efforts help those actively working, living and contributing to their communities to fully realize the benefits and responsibilities of citizenship. By definition, this work strengthens the connective tissue of our democracy. But I think it’s especially important now. Not because of some of the views regarding immigration that we’re seeing gain traction, but because those views are a symptom of a different kind of problem—the way that it has been harder for some people to find and to see common purpose with each other in communities and in our country.

In his seminal work on multiculturalism, the philosopher Charles Taylor noted that a key force in nationalist movements is the drive for recognition; the need to be recognized for who one is. Because it is in being seen as an African American or a white person; as a woman or a man; as an American or a Canadian that in some sense makes that identity true and real. Recognition is constitutive of our individual identities, and helps us to feel stable and validated as individuals.

Taylor argues that this force can’t be stifled. “Misrecognition shows not just a lack of due respect,” he writes, “It can inflict a grievous wound, saddling its victims with crippling self-hatred. Due recognition is not just a courtesy we owe people. It is a vital human need.” In some sense the defining challenge for democracy in the late 20th and early 21st centuries is to figure out a way to give everyone the recognition that they need in a society. That is because we are living in a moment when some feel—and they feel this genuinely—that recognition of others comes at their expense. And those feelings are making it harder and harder to be a society where different kinds of people can live together productively and peacefully amidst their differences.

In that context, it seems that a part of what is so important about the New Americans Campaign, and efforts to help legal permanent residents naturalize more generally, is that this process is about mutual recognition. It is a process in which a person says, “I want to be recognized. I want to be seen as an American. And, to do so, I know that I need to recognize the core, underlying values of this place. I know that I have work to do, responsibilities to discharge, and knowledge to acquire. And I’m willing to accept that process and to put the work in if you will then see me for who I am, and what I bring as American too.”

The challenge of finding a common purpose, of finding mutual recognition in a time of immense global change, is daunting. There are no simple solutions. But there are positive steps and your work is undoubtedly one of them. So this is where I will leave you. You are actively advancing and extending democracy’s promise. Yet you do so at a time when democracies around the world, including ours, face new threats and challenges. Because of your commitment to the idea of democracy, your investment in our democracy, and your knowledge we’re counting on you to help us to understand, navigate and face down those threats. Thank you for your tireless work.