Citizenship Grants: Local Governments Investing in Residents Who Are Pursuing Their Dreams

Explore More

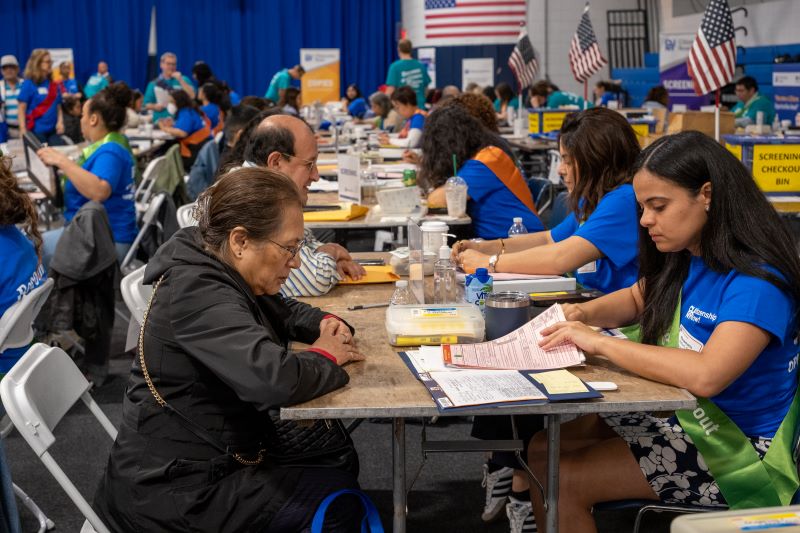

These are stressful times for immigrants in America: from the policing, detention, and deportation of immigrant families, to visa and citizenship processing delays, to the airwaves filled with hateful rhetoric. So when immigrant residents of Montgomery County, MD learn that their local government wants to make it easier for them to become U.S. citizens, they are often overwhelmed with gratitude and moved to tears, says Pablo Blank, CASA’s senior manager of immigrant integration programs. Blank has helped develop a pilot program, funded by the county, that awards grants to eligible residents who want to naturalize. “I expected that people would be grateful to get financial support to help them to apply for American citizenship,” says Blank. “But I wasn’t expecting how emotional they would be when they learned where the money came from. To know that their local government of the city or the county where they live was accepting them, and helping them to become citizens, was a very big deal for the people who received the scholarship.”

Across the country,

local governments are beginning to help employees and residents pursue a path

to citizenship. Some invite organizations onsite to assist eligible immigrants

with the citizenship process—providing English language classes, test preparation,

and application assistance. Others are experimenting with public-private

partnerships to offer “citizenship scholarships” or vouchers to defray the

expense associated with filing fees. Frequently, it is a partner from the New

Americans Campaign that runs classes and provides legal help.

Montgomery County, a suburb of Washington, D.C. has a population of 1.1 million, a third of whom are foreign born. Over 150 languages are spoken in the schools. “The world became a village here,” says Kaori Hirakawa, who manages the county’s direct services agency, called the Gilchrist Center for Cultural Diversity. A few years ago, the county joined forces with CASA to provide citizenship scholarships after a former county executive visited a naturalization workshop.

The number of volunteers and the diversity of the people applying for citizenship impressed the former official, says Blank, “He was able to talk to people, many of whom expressed how difficult it was to come up with the funds to afford the process.” The application’s expense is one of the largest obstacles to citizenship according to Blank. “Many LPRs (lawful permanent residents) would apply if they had the ability to pay the fee,” Blank told the executive. “When they come to consult with us, we often find that they are eligible for citizenship, but they do not qualify for the USCIS fee waiver. With no other options, they are discouraged and decide not to pursue their dream of becoming American citizens.” The county executive understood how important it is for residents to become citizens, says Hirakawa, “there are so many benefits.”

For

many Montgomery County, MD, residents the cost of living is high and, if their

pay is close to the minimum wage of $13 an hour, it is prohibitive to pay $725 for

the naturalization application fee. The USCIS will waive the fee for people

whose household income is below 150% of the federal poverty guideline. Even if a

person makes more than minimum wage, the fees add up quickly when several

family members apply for citizenship at the same time.

CASA presented a formal proposal to the county, citing the number of LPRs living in the county who might be helped, as well as studies about the beneficial impact of naturalization, including economic impact. The county agreed to fund a partial scholarship and asked CASA to administer the pilot program. In its first year, CASA received $50,000 from the county: $30,000 went into the scholarship fund and $20,000 went to the organization to conduct eligibility screenings and provide legal assistance. Information about the scholarship is shared on social media and, through word of mouth, by all the county’s community liaisons.

Anyone living in Montgomery County and making less than three times the federal poverty guideline (or $37,470 in 2019) is eligible to apply. If applicants do not qualify for USCIS assistance, the grant provides $300 towards the application fee of $750, and the applicant pays the rest. If the applicant gets partial assistance from the federal government, the grant provides $150 toward the fee. Forty scholarships have been awarded so far and CASA guides each recipient through the application process.

In nearby Washington, D.C. a different partnership with local government is taking root. Mayor Muriel Bowser collaborated with the National Immigration Forum to help eligible members of the city’s workforce apply for citizenship. The Forum’s program, New American Workforce, has brought citizenship services to the worksites of hundreds of big businesses around the country, as well as eight large city governments. “What’s unique this year,” says Jennie Murray, the director of integration programs at the National Immigration Forum, “is that Mayor Bowser asked how do we make this bigger and better? What are other employers doing?” When Mayor Bowser learned that Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber has a $25,000 citizenship fund, set up by his predecessor, to help eligible employees and family members pay the application fee, she was inspired to do it too. “She said, ‘I love that, and what I’d like to do is make it bigger,’” says Murray. So this year the District asked the Forum to administer a $100,000 fund to help D.C. resident workers, contractors and their family members pay $725 for the N400 citizenship application and biometrics fees.

DC’s citizenship fund is fortunate to have an easy way to get the word out. The city’s 60,000-member workforce has an established internal communications infrastructure and intranet to provide information to eligible workers. “It’s a valuable way of getting to the employees,” says Murray who estimates that 126 employees will be able to receive this financial help during its pilot year. The New American Workforce partners with many New Americans Campaign’s legal service providers who provide free screening, legal counsel and English language classes.

Pablo Blank finds getting the word out about the fund in Montgomery

County is much more challenging because they do not have a budget for

promotion. “That is one of the big lessons for the years to come,” he says,

“it’s important to have funding for advertising. We have been doing some

Facebook campaigns, and slowly we have been able to interest media outlets.” Blank

is inspired by the cooperation that The New American Workforce is getting from Washington,

D.C.’s human resources department. “I think that is a very powerful outreach

strategy,” says Blank who hopes that the County will also help spread the word

about the grants administered by CASA.

Other cities are

also experimenting with ways to support aspiring citizens. The City and County

of San Francisco’s Pathways to Citizenship Initiative administers a match fund that covers 50% of the citizenship application fee for

individuals who live or work in the city. Many local governments recognize that

there is direct correlation between immigrant integration and happier, more

secure, and more productive workers. “A lot of people who are new to this

country come from turmoil,” says Montgomery County’s Hirakawa, “with a huge

distrust of government.” So when they receive help paying for the citizenship

application, “It is one way of building trust with the county government.” She

sees many new citizens return to her agency to volunteer, “There’s a circle of

kindness, and community building, when you are given to —you give back. It’s

such a wonderful, wonderful thing to see.”

Research also shows that providing help with naturalization fees significantly speeds up the integration process. Stanford University’s Immigration Policy Lab studied a naturalization voucher program in NY State and learned that immigrants who received vouchers to defray application costs applied for citizenship at twice the usual rate. Only time will tell if that holds true in Montgomery County and Washington D.C. “Everyone is frightened now but, as a naturalized citizen myself, I see citizenship as probably the best way for immigrants to protect themselves.” Says Hirakawa, “As the manager of the county’s immigrant services agency, I would love to encourage more people to apply for citizenship so they can protect their lives in our county.”

The first Washington D.C. district employees were awarded their

naturalization grants in June as Mayor Bowser launched Immigrant Heritage Month.

“We’re proud of the investments we’ve made to help residents pursue their

dreams of becoming American citizens,” the mayor told the crowd. “Washington, D.C.

is a stronger and more vibrant city because of the contributions of thousands

of immigrants who live in our community.”