Carl Bergquist: Just two days before my oath ceremony, I learned that USCIS offices were closed and everything was canceled due to COVID-19.

Explore more

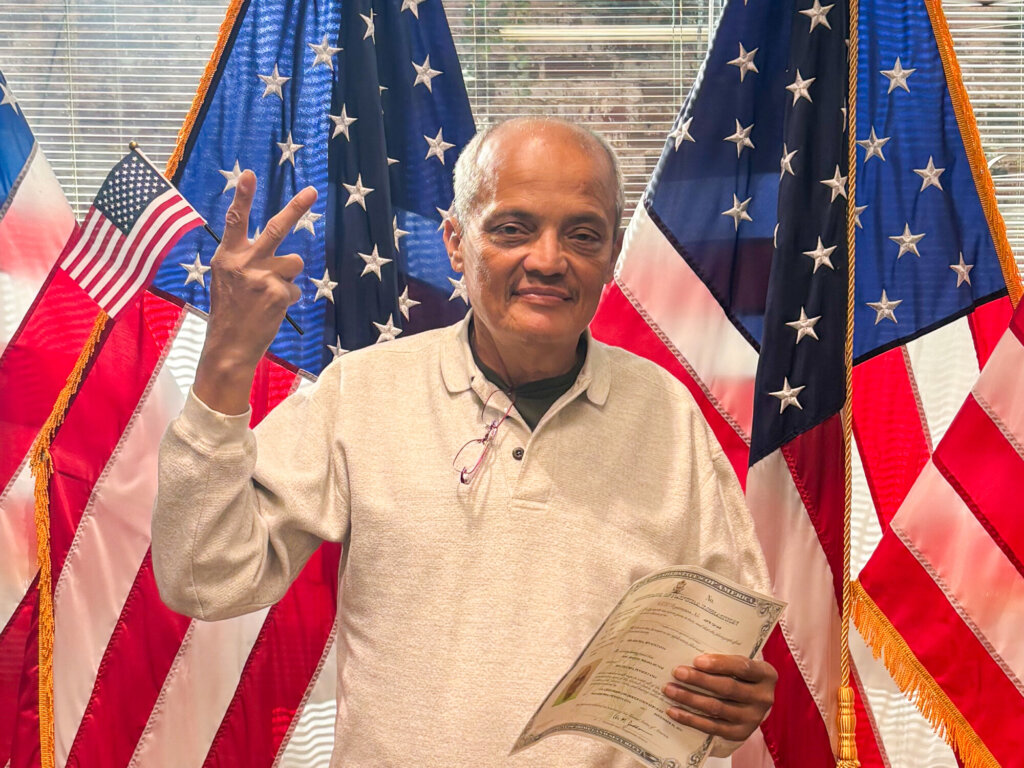

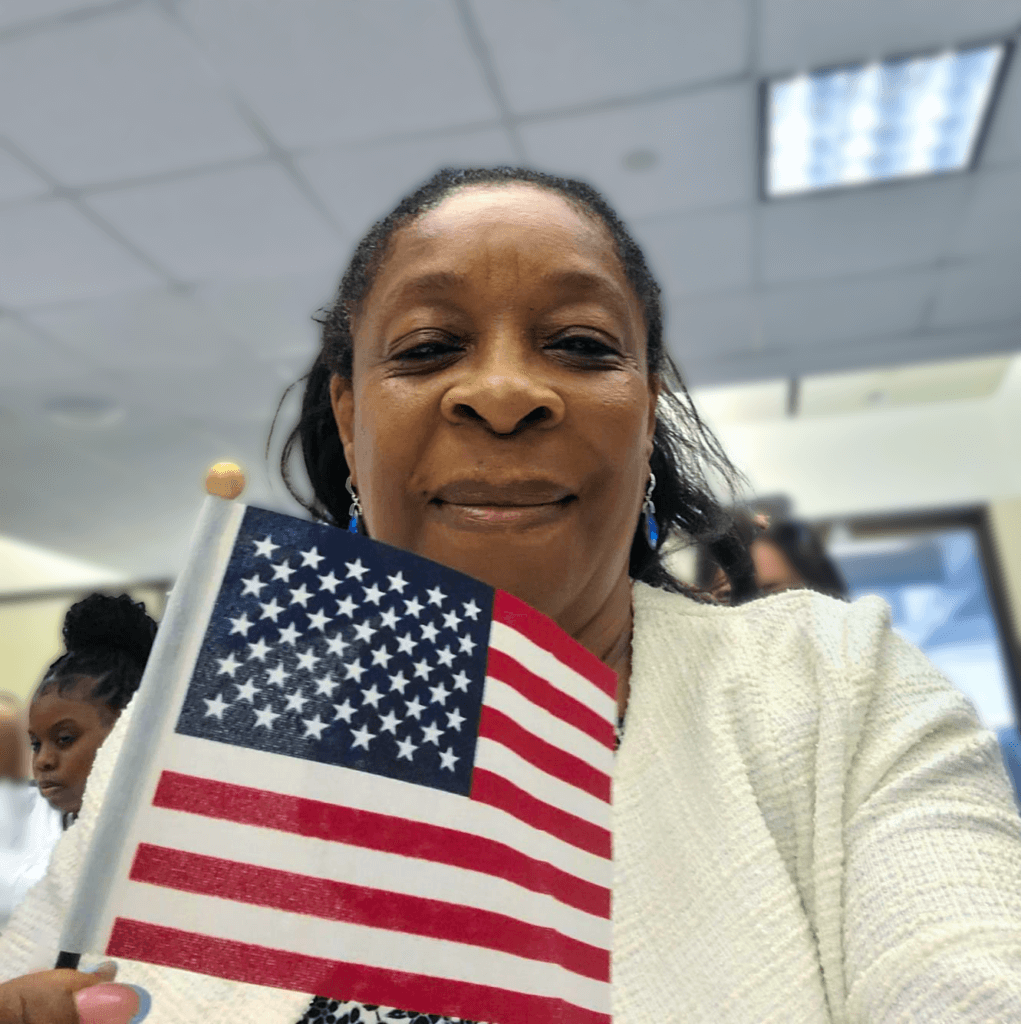

(Photo courtesy of Carl Bergquist)

I’m originally from Stockholm, Sweden. I first moved to the United States when I was six years old. My father was a diplomat in the Swedish foreign service. His first posting abroad after my brother and I were born was in Washington, DC. I had just turned six, my brother was four, and we were thrown into the public school system. In terms of the big American melting pot, I think people talk about the military and the public school system as institutions that really foster American identity. We were very young, and we became little, quasi-Americans, making the pledge of allegiance to the flag every morning. We lived in the United States for five years, but it was a trying time toward the end because my mother became ill and passed away. The fact that she passed away in the U.S. and that’s the last we saw her meant I have always felt a strong connection to this country.

We returned to Sweden and I lived there many years. I finished high school, completed my military service, and I began university. I felt a yearning to go back to the United States to live. I was still comfortable with the language and the culture. I had gone to an English language school the whole time, so my language skills were good. I consumed books, media, and music in English. I got into Georgetown University as a transfer student and I felt totally comfortable with a lot of the American kids in my dorm, as well as with the international students—I was used to living in-between. After I graduated, I moved back to Sweden to work and go to graduate school. I was living in Berlin, working for a think tank, when I met my now-wife. She’s American, from Maryland. We spoke German in the office, and I thought she was German because she spoke better German than I did, with less of an accent. She thought I was American because in German I had an American accent. At first, she didn’t want anything to do with me, because she wanted to meet non-Americans while she was living abroad. When she learned I wasn’t an American she gave me the time of day and we began dating. We had a transatlantic relationship for a few years, until she got into a PhD program at UCLA in Los Angeles.

(Photo courtesy of Carl Bergquist)

It was in Los Angeles that we decided to get married. I went

through that whole process of being sponsored by my partner, waiting in Sweden,

securing a fiancé visa, and then getting married within the 90 days after

arrival that’s required to apply for a green card. When you get your green card

through a recent marriage, you have to reapply after two years to remove

conditions on the green card, so we did that. Some people naturalize

immediately when they become eligible, but my wife was about to graduate, and

we were about to move to Texas for her post-doc, so I didn’t feel a rush. I

knew that if you move after you submit your application it can delay the

process because your file has to move as well. I thought, “Nah, I’ll do it

later.” But while we were living in

Austin, we had our first child; so again, it didn’t happen. We moved to

Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, for my wife’s first academic job and I thought about

applying then, but my second daughter was born, and I was busy with family, and

work, and I began law school. So, I just didn’t get around to it. Years went by

and now we’re in Ohio.

A couple of things changed for me here. I am now a policy counsel with CHIRLA, the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, which is a Los Angeles-based, California statewide organization that I worked for earlier, when I lived in Los Angeles. I was in the process of rejoining them in 2019 and it reconnected me with the communities of immigrants who are fighting for their own opportunity to live and work in this country. I am inspired every single day by CHIRLA’s members, especially the DREAMer youth who lead the way in fighting for not just for their own rights but for those of their families and all other immigrants.

Not only did I appreciate that I was eligible to become a U.S.

citizen, I also wanted to be able to vote and to serve on a jury. But we were

about to move again, this time to Ohio from Hawaiʻi. I talked with my

professor, John Egan, who heads the immigration clinic at the University of

Hawaiʻi at Mānoa William S. Richardson School of Law,

about beginning the process there and transferring the file to Ohio. We

looked at the different wait times and, by sheer coincidence, I was moving to

an area served by the Cleveland USCIS field office and it had one of the

shortest wait times in the entire U.S. There is only a three-month processing

time in Cleveland, so it was better to wait until I moved to Ohio. This past

November, I heard about the devastating immigration fee increases proposed by

the Trump Administration and I was finally propelled to act. I applied in

December, just before the winter holidays in 2019, and it went really, really

quickly.

I had my interview at the end of February. I was told right

then and there that I passed the language test and the civics test. At the

time, there was definitely talk about the coronavirus, but it was early. There

were some signs up at the Federal building about washing your hands, but

nothing more than that. A few days later, I got a notice that my oath ceremony

was scheduled for March 20. That would have been less than three months after I

submitted my application! It was just two days before my ceremony, when I

learned that USCIS offices were closed as of March 18 and everything was

canceled. Ohio was the first state to close all the schools. Our life went

ahead, but we were all on lockdown. So, we’ve been isolating a long time.

Because of my work, I knew that June 4 was the day that the USCIS offices would

open again. On that day, I missed a call from Cleveland. They called again the

next day and it was someone from USCIS who asked if I could come to an oath

ceremony on June 11.

I live in Toledo, two hours away. So, I drove four hours

round trip. There were 20 of us. There was absolutely no pomp and circumstance.

They set up 20 chairs that were physically distant and we had to wear our

masks. The USCIS staff were very kind. The supervisor congratulated us and

explained that he wasn’t going to show any of the videos. We took the oath of

allegiance and afterward he called us up, one by one, to get our naturalization

certificates. He didn’t state nationalities, but he said the names out loud

before people walked up and I made educated guesses. It was a room of people

from all over the world. That was gratifying to see. If I’d walked into a room

and it was filled with people just like me, I would have been terrified.

(Photo courtesy of Carl Bergquist)

The entire ceremony was very short, not more than 15

minutes. It was perhaps even more low key than I expected, but regardless I

thought, “This is happening. This is the moment! This is so important to me.”

I’m a privileged, white male, who is usually not afraid to voice his opinion,

and usually does not suffer any consequence for doing so. But I also know

immigration law. I know what can happen behind the scenes. I know some people’s

applications are slow walked without anyone knowing what’s happening. I didn’t

take anything for granted, and it was a relief that the ceremony actually

happened. Thinking about the rights and responsibilities that come with

citizenship more than makes up for the absence of the pomp and circumstance.

More than the ceremony, gaining citizenship is momentous.

To that point, I’m very mindful of the fact that I’m here as a citizen because I married an American whose parents immigrated to the United States from Thailand. That was only possible because the laws were changed in 1965 to remove the national origins quotas and to be less racist. It’s also not lost on me that many of my ancestors emigrated to the United States from Sweden and were welcomed because they were white. But they were no different than the undocumented today. My driving force is that we return to the spirit that allowed my ancestors to migrate to the United States without facing discrimination and improve the system that permitted my partner’s parents to immigrate. It’s hard to believe we’ve drifted so far away from that.

Since applying for citizenship, and getting more immersed in my job, becoming acutely aware of what’s happening to the immigrant community—and more recently, the movement for black lives, I am more mindful than ever of my own privilege as a white male. This political moment made my decision to naturalize feel urgent to me personally. With this great power comes great responsibility, right? I want to be as involved as I can be. My right to vote and the responsibility to make myself available for jury duty will be dedicated to achieving justice for all. I feel it’s my responsibility. I do regret that I didn’t naturalize earlier, but at this point in time, it’s more important than ever. After I drove home, two hours, from Cleveland, I was greeted by my two daughters, who are six and three years old. They were very excited, and they said, “Welcome my American!”