Anuj Gurung: “I have a home that I was born into, and I have a home that I have built here in the U.S.”

Explore more

I was born in Kathmandu, which is the capital city of Nepal. I came to the United States in the fall of 2004 to begin college in Ohio. Like most immigrants who search for something better, I wanted to be the best version of myself. I wanted to explore what to study, as well as what kind of career I wanted to choose. A lot of South Asian societies are very communitarian. Sometimes it is difficult to find yourself individually. For me, the path was through education. I wanted to see how far my education would take me. I’ve always been a good student, so an undergraduate degree led to a master’s, a master’s to a PhD, and here I am.

My father is a retired police officer, and my mom was a nurse a long time ago. My family was always very ambitious in regards to education and that was one of the reasons why they supported my pursuit of higher education in the United States of America. It also helped that I got a scholarship that helped me afford my education. My understanding of American society was pretty rudimentary before I came. It was based on the movies that we saw in the late nineties, early 2000s and a few shows that took place in New York or Los Angeles.

I had little conception of rural America. I was surprised to find my liberal arts college was in the middle of nowhere, far away from other urban spaces. I learned that is the case in a lot of places in the United States, and I realized how vast America is. I had a fairly good education in Kathmandu. I learned English. The fluency I have today came with time; the language part wasn’t really that difficult. The cultural adaptation was more challenging. I was lucky that the college had a fairly significant international student population, and we created our own community. But I was one of those students who wanted to learn a lot about American society and culture. I never realized there would be so much diversity within American students. I enjoyed learning about America through my friends, my colleagues, and my teachers.

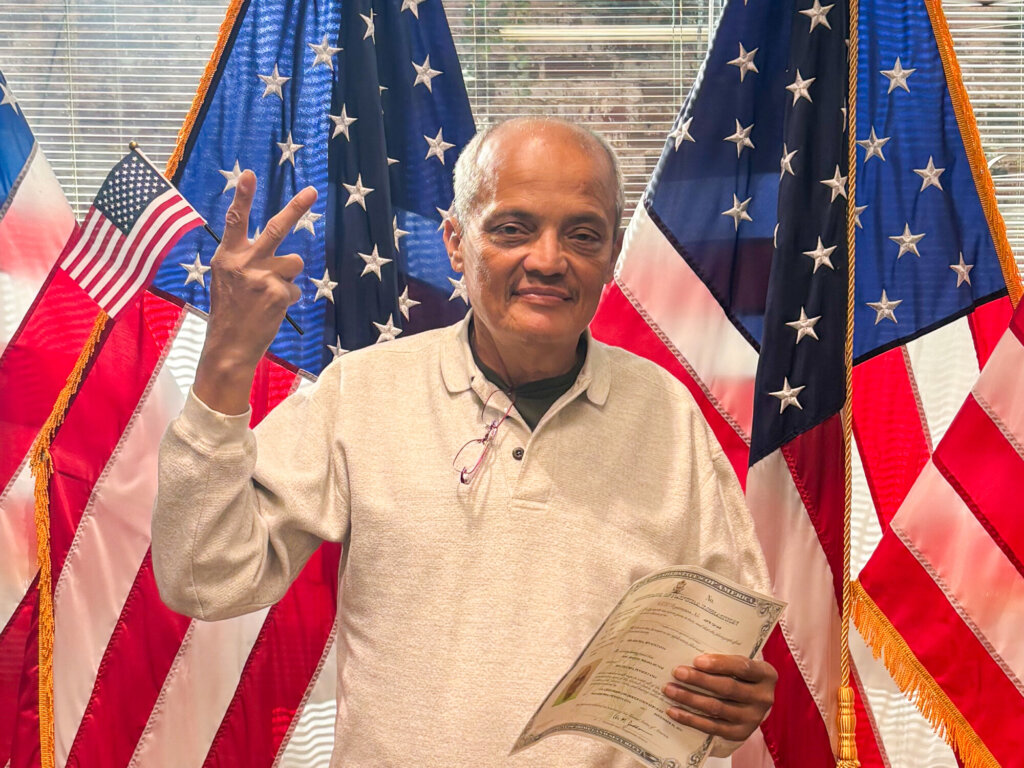

(Photo courtesy of Anuj Gurung)

After college, I went to Georgetown University for my master’s in a program on conflict resolution. This led to a PhD in political science at Kent State University, also with a focus on conflict resolution. While I worked on my master’s, I had the opportunity to return to Nepal to intern with the United Nations Refugee Agency. I helped Bhutanese refugees plan their journey to places like Akron, OH. I wanted to know how they were doing. My academic interests and my own experience as an immigrant were intersecting. I began research for my PhD, exploring how refugees adapt. Bhutanese refugees culturally and linguistically are very similar to people like me, but they don’t have the same privileges as I did as an accepted member of a country.

I had heard about International Institute in Akron, Ohio, and I wanted their perspective. They were very generous and allowed me to work with them. I learned a lot about how refugees adapt to American society. I also saw how institutions like International Institute have been proactively easing that transition. Citizenship is not a straight line; it’s not a direct option. As soon as you land in the United States, you have to wait. You go through your green card process and so on. The people I spoke to for my research were at different levels of applying for citizenship. People who are educated, business owners, community leaders, and others who have a knowledge of the system are always at the head of the line. The people who lag behind are the refugees who struggle with their language skills as well as their education.

I’m Nepali. I was 20 years old when I first came to United States of America. I’m always going to have Nepali roots. However, having lived here for more than 10 years, I also see myself in American terms. Culturally, I’m very much an American. I know what it means to grow up here. I always tell my wife that I learned how to be who I am in America, on my own, away from my Nepali family. I have a deep attachment to the American society. I like to say that I have a home that I was born into, which is Nepal. And I have a home that I have built here in the United States of America. I have more than one home, I have more than one identity.

I understand people may feel that acquiring American citizenship seems like you are turning your back on your native society. I don’t see it that way. I consider America home just as I consider Nepal home. I’ve lived here for a long time and I have learned that, in a lot of ways, who I am comes from my experiences in American society. I have established roots here; I’m married to an American woman I met in college. My wife is from Ohio. Applying for citizenship was the culmination of various conversations we had discussing what it means to be here together and to have a family one day. It wasn’t a difficult decision per se, but we took a long time. Another reason I’m trying to get my citizenship is that we both have ambitions of traveling once the pandemic has settled down. We both love traveling. The U.S. passport will make it so much easier for us to travel together.

My wife always says that she wants me to get citizenship because I am more informed than a lot of the people who vote. I consider myself very informed politically. I teach political science conflict resolution courses. So it is frustrating that my participation in civics and politics is not a direct one. All I can do is talk about it. It would be a privilege to be able to participate directly in the democratic process of the United States of America.

I started conversations about pursuing citizenship with the International Institute because I had read about a deadline in October last year when the fees were going to go up. We had already come to the point emotionally and spiritually, and we knew I was going to apply. Then I realized that we might save money and avoid some unnecessary obstacles. Most of the application was pretty straightforward. The International Institute is very, very professional and very capable, and they helped me with details here and there. Some of my friends also began the process after living through a couple of years where they were challenged as immigrants. They may have had a green card, but there was uncertainty as to what kind of restrictions we might expect in the future. It was also was a moment of defiance, like “we’ve been here, we’ve contributed our energy economically and spiritually—we came here, we built communities, we built our homes here from scratch—we have a stake in this society too.”

The refugees that I work with generally understand it is important to be a citizen; they don’t have to be convinced. Remember, refugees lived through the experience of not belonging somewhere and have been denied citizenship and the identities they preferred. I think the bigger challenge is to adequately prepare some refugees who may have language constraints, or who may not be at ease with the structure of the test. That’s the biggest challenge.

I submitted my application last September and the most recent estimate for the interview is at the end of the summer. I’m looking forward to the taking the oath. I’m sure I will feel proud. The ceremonial aspect of oathtaking, I think is very spiritual and very meaningful. My wife is as much involved in the process as I am. I think witnessing my immigrant experience from her American eyes has been a very interesting and, at times, frustrating experience for her as well. We are both very much looking forward to me getting my U.S. citizenship. I think my wife is secretly planning a party.