What USA Learns learned during the Covid-19 pandemic

Explore more

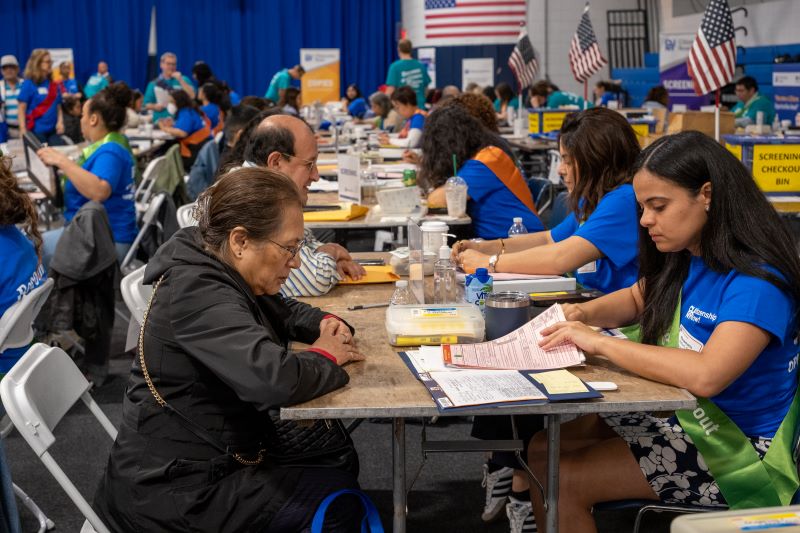

Last year, teachers of adult English language and U.S. citizenship classes had to pivot quickly when the pandemic hit. Instructors tried to maintain forward momentum and keep students engaged virtually, despite daunting obstacles. When USCIS offices were closed and citizenship workshops were canceled, the naturalization process stalled, and the backlog soared. To add to the challenges, a new U.S. citizenship test was looming.

(Photo courtesy of Andrea Willis)

When everyone first went remote, “It was just boom! The doors of schools were closed,” says Andrea Willis, director of Internet and Media Services at the Sacramento County Office of Education. “We had teachers who quickly had to scramble to figure out how to continue providing instruction to their learners in this new way that many of them were not used to.” Gone was the attentive class, the white board, and the markers. “It was a quick and kind of wild and crazy transition for both teachers and learners,” says Willis. While everyone scrambled to move to the internet, USA Learns, the online tool that Willis and her colleagues first developed in 2008, was the right tool for the moment. “USA Learns was in a good position to be a free online resource that’s high quality and very easy to use,“ says Willis.

When it launched in 2008, USA Learns was an English language learning tool for independent learners and adults studying with a teacher. In 2017 Willis and her colleagues added a citizenship course that helps applicants prepare for all aspects of the naturalization interview and U.S. citizenship test. Content was developed in collaboration with the Immigrant Legal Resource Center and the New Americans Campaign. “We want applicants to be able to arrive to the USCIS building and know what they’re doing—for example, as they walk through security, what are those words they might hear like ‘empty your pockets, stand in line, go to the fourth floor.’ We want them to know all the vocabulary that goes with everything from the N-400, to the civics section, to what to expect before and after the interview.”

(Photo courtesy of Jennifer Gagliardi)

Jennifer Gagliardi, an ESL and Citizenship Instructor at Milpitas Adult School in San Jose, CA was an adviser to, and early adapter of, the USA Learns citizenship course. She says that while there may be other good resources to study for the citizenship test, no other course teaches the language of the N-400 better than USA Learns. “People don’t fail on civics content,” Gagliardi says, “they almost always fail on the N-400 part because they think that when they go to the interview all they will be asked are the civics question. They memorize the 100 questions, but they can’t answer the gatekeeping questions: What is your middle name? What is your phone number? Explain to me how you are eligible to become a U.S. citizen.”

When Gagliardi, who teaches in the heart of Silicon Valley, was locked down by the pandemic, she was uniquely prepared to teach online; she already had an online blog, recorded podcasts and made YouTube video teaching tools. “For me to go into lockdown on March 13th was no big deal,” she says. “The steep learning curve was how to share on Zoom.” She also had to adjust her classroom teaching to what works in a Zoom classroom where students can become more passive. Gagliardi finds that, with encouragement, her students are becoming much more adept at using online learning tools.

Willis also sees the growing confidence of online learners reflected in the USA Learns metrics. When the in-person classes shut down last spring, there was an increase of 79% in the people who started using the U.S. citizenship course compared to last year, says Willis. They also spend more time on the site. She reports, “We had a 31% increase in the number of hours they spend there.” Willis concludes that “Many teachers who had been teaching face-to-face previously had to hurry up and find some way of continuing their instruction online. We think a lot of those in-person teachers quickly converted to teaching with USA Learns as part of their class.” Teachers can set up a virtual classroom on the teacher side of USA Learns that students sign into with a class code. The teacher has access to a class roster, an account of the time students spent completing the activities, and their scores.

During the first months of lockdown Willis did several dozen trainings with teachers to help them get up and running with the program. After analyzing the increased traffic, Willis also learned that many of their learners come to their site on their phones, and study on their phones. “You can do it,” she says, “but it is a more frustrating experience than it should be.” Consequently, Willis began a redesign of the site for mobile phones, thanks to a grant from the Dollar General Literacy Foundation. The redesigned site will launch this fall.

Moving online throughout the spring was not the only challenge. Teachers who were preparing their students for the U.S. citizenship test confronted a new shockwave to their community after the USCIS announced they had doubled the high stakes U.S. civics test to 20 questions rather than 10, with 128 study questions rather than 100. The revision of the U.S. citizenship test had been in the works since 2018 to keep the test “current and relevant,” according to the USCIS. USCIS announced the new test last November, telling teachers and students that it would go into effect on December 1. The agency maintained that they relied “on input from experts in the field of adult education to ensure that this process is fair and transparent.” But some of those experts themselves were taken aback when they saw that much of the input that they worked hard to provide during the previous year was disregarded. Critics of the longer, more complicated test believed it was an effort to create new obstacles to immigration and to inject a conservative bias in the questions and answers. Others were concerned that a longer, more complicated test would discourage people from seeking citizenship.

Citizenship teachers “freaked out,” says Gagliardi. “I was shocked when I saw it. I thought this can’t stand. That was my response. They’re going to have to change this because it’s so blatantly wrong.” Gagliardi didn’t begin working with her students on the new content because many of her students had applied before the cutoff for the new test and would be allowed to take the old version. “The students were not worried,” says Gagliardi, “the teachers and the book publishers were worried.” Gagliardi herself didn’t change her teaching content. “I really felt that USCIS would do the right thing and not go forward with the test. USCIS has reconsidered its position before.”

Willis, as the USA Learns developer, was not so sure. “I was freaking out,” she says. “I have this beautiful, amazing course. My whole unit three is very carefully crafted around those 100 questions. Then overnight they were going to become obsolete.” Various ESL teachers, however, counseled Willis not to start making any changes. “They were saying, ‘go slow, we think those questions are going to be revoked.’” Regardless, Willis didn’t have the budget to change her online program. It would have cost as much as $100,000 to remake the animations that teach the 100 civics questions. “So, I just waited.” She says, “I was crossing my fingers. We are now going to go back to the old questions and I’m so happy.”

This past February, after many challenges from the naturalization assistance community, the USCIS announced it would revert to the 2008 version of the naturalization civics test. “A new citizenship test is not life and death,” says Gagliardi. “There was a pause on green cards for a year. There was the Muslim ban. There are the problems on the border. That stuff is life and death.” But Gagliardi thinks that the civics test really informs who we are as United States citizens. “The new test did not look like America,” she says. It did not look like the people that she serves. “The new test was much more representative of a white America, in which everyone comes from Plymouth Rock,” she says. “That is not America.”